Chapter 4 Web scraping

Today there are more than 3.7 billion Internet users, which almost 50% of the entire population (Internet World Stats 2017). Taking into account all the existing Internet-enabled devices, we can estimate that approximatelly 30 billion devices are connected to the internet (Deitel, Deitel, and Deitel 2011).

In this chapter we focus on Web data extraction (Web scraping) - automatically extracting data from websites and storing it in a structured format. However, the broader field of Web information extraction also requires the knowledge of natural language processing techniques such as text pre-processing, information extraction (entity extraction, relationship extraction, coreference resolution), sentiment analysis, text categorization/classification and language models. Students that are interested in learning more about these techniques are encouraged to enrol in a Natural language processing course. For introduction to natural language techniques please see the Further reading references (Liu 2011) (Chapter 11), (Christopher, Prabhakar, and Hinrich 2008) (Chapters 12, 13, 15-17, 20), (Aggarwal and Zhai 2012) (Chapters 1-8, 12-14) or other specialized books on natural language processing.

4.1 Introduction to Web data extraction

Web data extraction systems (Ferrara et al. 2014) are a broad class of software applications that focus on extracting data from Web sources. A Web data extraction system usually interacts with a Web source and extracts data stored in it: for example, if the source is an HTML Web page, the extracted content could consist of elements in the page as well as the full-text of the page itself. Eventually, extracted data might be post-processed, converted to the most convenient structured format and stored for further usage. The design and implementation of Web data extraction systems has been discussed from different perspectives and it leverages on scientific methods from different disciplines including machine learning, logic and natural language processing.

Web data extraction systems find extensive use in a wide range of applications including the analysis of text-based documents available to a company (like e-mails, support forums, technical and legal documentation, and so on), Business and Competitive Intelligence, crawling of Social Web platforms, Bioinformatics and so on. The importance of Web data extraction systems depends on the fact that a large (and steadily growing) amount of data is continuously produced, shared and consumed online: Web data extraction systems allow us to efficiently collect these data with limited human effort. The availability and analysis of collected data is vital to understanding complex social, scientific and economic phenomena which generate the data. For example, collecting digital traces produced by users of social Web platforms such as Facebook, YouTube or Flickr is the key step to understand, model and predict human behavior.

In commercial fields, the Web provides a wealth of public information. A company can probe the Web to acquire and analyze information about the activity of its competitors. This process is known as Competitive Intelligence and it is crucial to quickly identify the opportunities provided by the market, to anticipate the decisions of the competitors as well as to learn from their faults and successes.

The challenges of Web data extraction

In its most general formulation, the problem of extracting data from the Web is very hard because it is constrained by several requirements. The key challenges we can encounter in the design of a Web Data Extraction system can be summarized as follows:

- Web data extraction techniques implemented in a Web data extraction system often require human input. The first challenge consists of providing a high degree of automation by reducing human efforts as much as possible. Human feedback, however, may play an important role in raising the level of accuracy achieved by a Web data extraction system. A related challenge is to identify a reasonable tradeoff between building highly automated Web data extraction procedures and the requirement of achieving accurate performance.

- Web data extraction techniques should be able to process large volumes of data in relatively short time. This requirement is particularly stringent in the field of Business and Competitive Intelligence because a company needs to perform timely analysis of market conditions.

- Applications in the field of Social Web or, more in general, those dealing with personal data, must provide solid privacy guarantees. Therefore, potential (even if unintentional) attempts to violate user privacy should be timely and adequately identified and counteracted.

- Approaches relying on machine learning often require a large training set of manually labeled Web pages. In general, the task of labeling pages is time comnsuming and error prone and, therefore, in many cases we cannot assume the existence of labeled pages.

- Often, a Web data extraction tool has to routinely extract data from a Web Data source which can evolve over time. Web sources are continuously evolving and structural changes happen with no forewarning and are thus unpredictable. In real-world scenarios such systems have to be maintained, because they are likely to eventually stop working correctly, in particular if they lack the flexibility to detect and face structural modifications of the target Web sources.

The first attempts to extract data from the Web date back to the early 90s. In the early days, this discipline borrowed approaches and techniques from Information Extraction (IE) literature. In particular, two classes of strategies emerged: learning techniques and knowledge engineering techniques – also called learning-based and rule-based approaches, respectively. These classes share a common rationale: the former was thought to develop systems that require human expertise to define rules (for example, regular expressions) to successfully accomplish the data extraction. These approaches require specific domain expertise: users that design and implement the rules and train the system must have programming experience and a good knowledge of the domain in which the data extraction system will operate; they will also have the ability to envisage potential usage scenarios and tasks assigned to the system. On the other hand, also some approaches of the latter class involve strong familiarity with both the requirements and the functions of the platform, so human input is essential.

4.2 Web wrapper

In the literature, any procedure that aims at extracting structured data from unstructured or semi-structured data sources is usually referred to as a wrapper. In the context of Web data extraction we provide the following definition:

Web wrapper is a procedure, that might implement one or many different classes of algorithms, which seeks and finds data required by a human user, extracting them from unstructured (or semi-structured) Web sources, and transforming them into structured data, merging and unifying this information for further processing, in a semi-automated or fully automated way.

Web wrappers are characterized by a 3-step life-cycle:

- Wrapper generation: the wrapper is defined and implemented according to one or more selected techniques.

- Wrapper execution: the wrapper runs and extracts data continuously.

- Wrapper maintenance: the structure of data sources may change and the wrapper should be adapted accordingly.

The first two steps of a wrapper life-cycle, generation and execution, might be implemented manually, for example, by defining and executing regular expressions over the HTML documents. Alternatively, which is the aim of Web data extraction systems, wrappers might be defined and executed by using an inductive approach – a process commonly known as wrapper induction (Kushmerick, Weld, and Doorenbos 1997). Web wrapper induction is challenging because it requires high-level automation strategies. Induction methods try to uncover structures from an HTML document to form a robust wrapper. There exist also hybrid approaches that make it possible for users to generate and run wrappers semi-automatically by means of visual interfaces.

The third and final step of a wrapper’s life-cycle is maintenance: Web pages change their structure continuously and without forewarning. This might affect the correct functioning of a Web wrapper, whose definition is usually tightly bound to the structure of the Web pages adopted. Defining automated strategies for wrapper maintenance is vital to the correctness of extracted data and the robustness of Web data extraction platforms. Wrapper maintenance is especially important for long-term extractions. For the purposes of acquiring data in a typical data-science project, wrappers are mostly run once or over a short period of time. In such cases it is less likely that a Web site would change, so automation is not a priority and is typicaly not implemented.

4.2.1 HTML DOM

HTML is the predominant language for implementing Web pages and it is largely supported by the World Wide Web consortium. HTML pages can be regarded as a form of semi-structured data (even if less structured than other sources like XML documents) in which information follows a nested structure. HTML structure can be exploided in the design of suitable wrappers. While semi-structured information is often also available in non-HTML formats (for example, e-mail messages, code, system logs), extracting information of this type is the subject of more general information extraction and not the focus of this chapter.

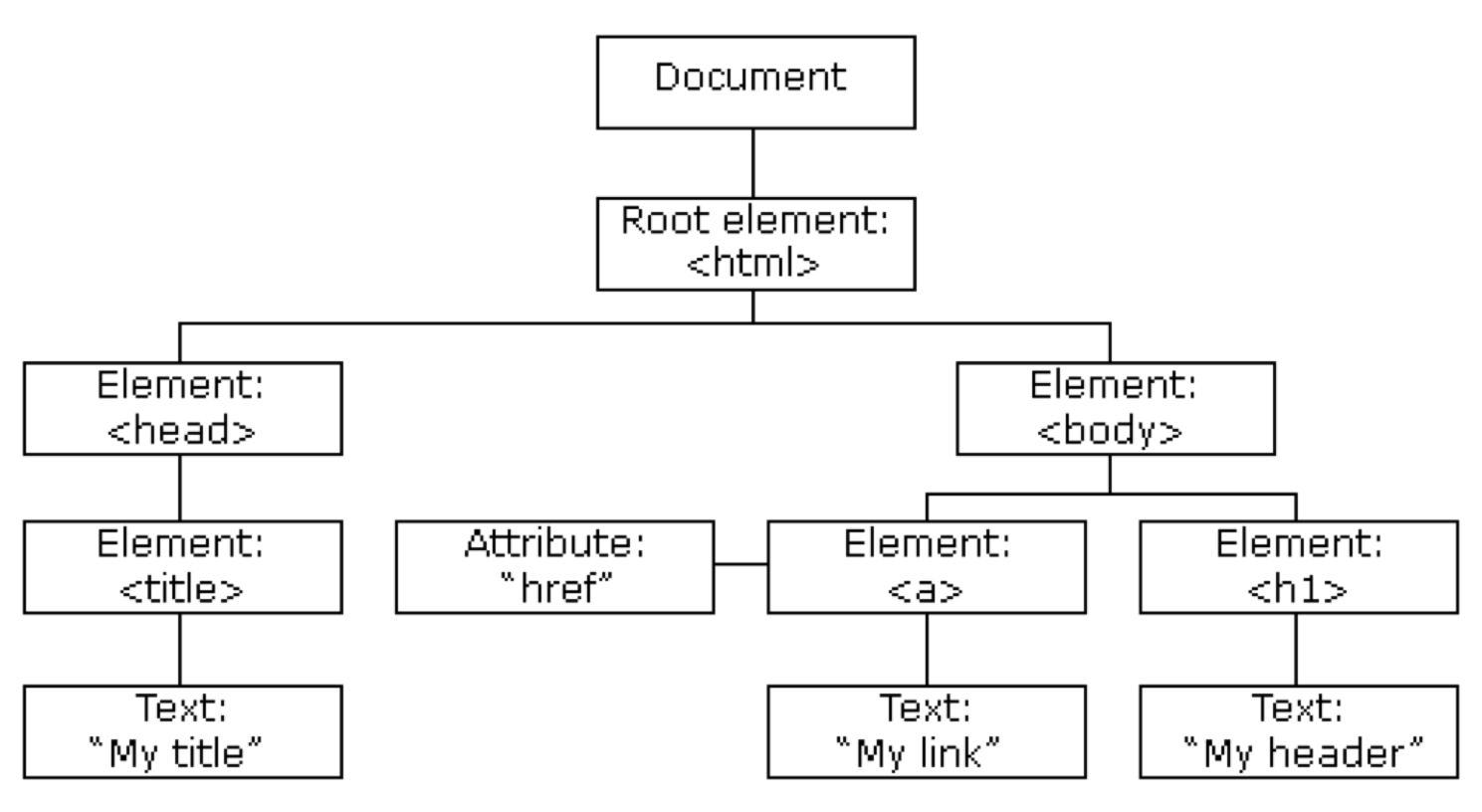

The backbone of a Web page is a Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) document which consists of HTML tags. According to the Document Object Model (DOM), every HTML tag is an object. Nested tags are called children of the enclosing tag. Generally we first parse a web page into a DOM tree representation. Then we specify extraction patterns as paths from the root of the DOM tree to the node containing the values to extract. Special languages such as XPath or XQuery support searching and querying elements of a DOM tree.

Below we show a simple HTML Web page and its representation as a HTML DOM tree.

<html>

<head>

<title>My Title</title>

</head>

<body>

<a href="">My link</a>

<h1>My header</h1>

</body>

</html>

Figure 4.1: DOM tree representation of the above HTML Web page.

The HTML DOM is an Object Model for HTML and it defines:

- HTML elements as objects.

- Properties for all HTML elements.

- Methods for all HTML elements.

- Events for all HTML elements.

Interactive Web pages mostly consist of Javascript code which is executed directly in the Web browser. The HTML DOM is also an API (Programming Interface) for JavaScript that allows it to dynamically:

- Add/change/remove HTML elements/attributes/events.

- Add/change/remove CSS styles.

- React to HTML events.

4.2.2 XPath

One of the main advantage of the adoption of the Document Object Model for Web Content Extraction is the possibility of exploiting the tools for XML languages (and HTML is to all effects a dialect of the XML). In particular, the XML Path Language (XPath) provides with a powerful syntax to succintly address specific elements of an XML document. XPath was also defined by the World Wide Web consortium, as was DOM.

Below we provide an XML example to explain how XPath can be used to address elements of a Web page.

<persons>

<person>

<name>John</name>

<height unit=”cm”>191</height>

<sport>Running</sport>

<sport>Cycling</sport>

</person>

<person>

<name>Mandy</name>

<height>140</height>

<sport>Swimming</sport>

</person>

</persons>There exist two possible ways to use XPath: (A) to identify a single element in the document tree, or (B) to address multiple occurrences of elements. We show some XPath queries against the above XML document:

/persons/person/name- Extract all elements in the provided path. The result is<name>John</name>and<name>Mandy</name>./persons/person/name/text()- Get contents of all the elements that match the provided path. The result isJohnandMandy.//person/height[@unit="cm"]/text()- Extract contents of all height objects that have set attribute unit to cm and have their parent element named as person. Result is191.//sport- Extract all elements that appear at any level of XML and are named sport. The result is<sport>Running</sport>,<sport>Cycling</sport>and<sport>Swimming</sport>.//person[name="Mandy"]/sport/text()- Extract contents of sport objects that are nested directly under person objects which contain a name object with value Mandy. The result isSwimming.

The major weakness of XPath is its lack of flexibility: each XPath expression is strictly related to the structure of the Web page. However, this limitation has been partially mitigated with the introduction of relative path expressions. In general, even minor changes to the structure of a Web page might corrupt the correct functioning of an XPath expression defined on a previous version of the page. Still, due to the ease of use, many Web extraction libraries support the use of XPath in to addition of their own extraction API.

Let us consider Web pages generated by a script (e.g. the information about a book in an e-commerce Web site). Now assume that the script undergoes some changes. We can expect that the tree structure of the HTML page generated by that script will change accordingly. To keep the Web data extraction process functional, we should update the expression every time the underlying page generation model changes. Such an operation would require a substantial human effort and would therefore be very costly. To this end, the concept of wrapper robustness was introduced. From the perspective of XPath the idea is to find, among all the XPath expressions capable of extracting the same information from a Web page, the one that is least influenced by potential changes in the structure of the page and such an expression identifies the more robust wrapper. In general, to make the entire Web data extraction process robust, we need tools allowing for measuring document similarity. Such a task can be accomplished by detecting structural variations in the DOM trees associated with the documents. Techniques called tree-matching strategies are a good candidate to detect similarities between two trees (Tai 1979). The discussion of these techniques is outside the scope of this chapter.

4.2.3 Modern Web sites and JS frameworks

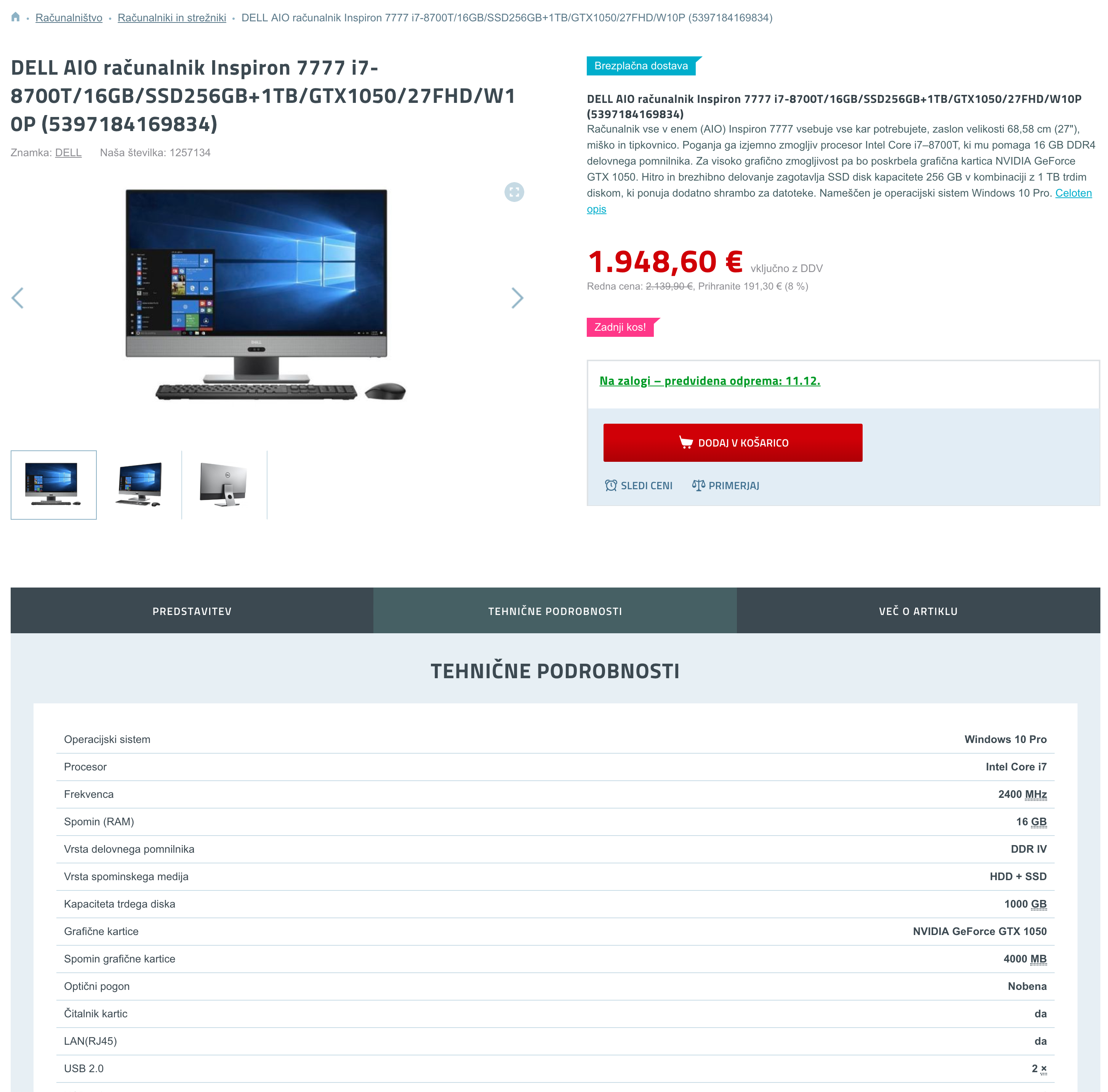

Modern Web sites still use HTML to render their data within Web browsers. Below we show an example of a Web page (left side) and extracted content from it (right side). When all pages follow the same structure, we can easily extract all the data.

|

|

|

|

|

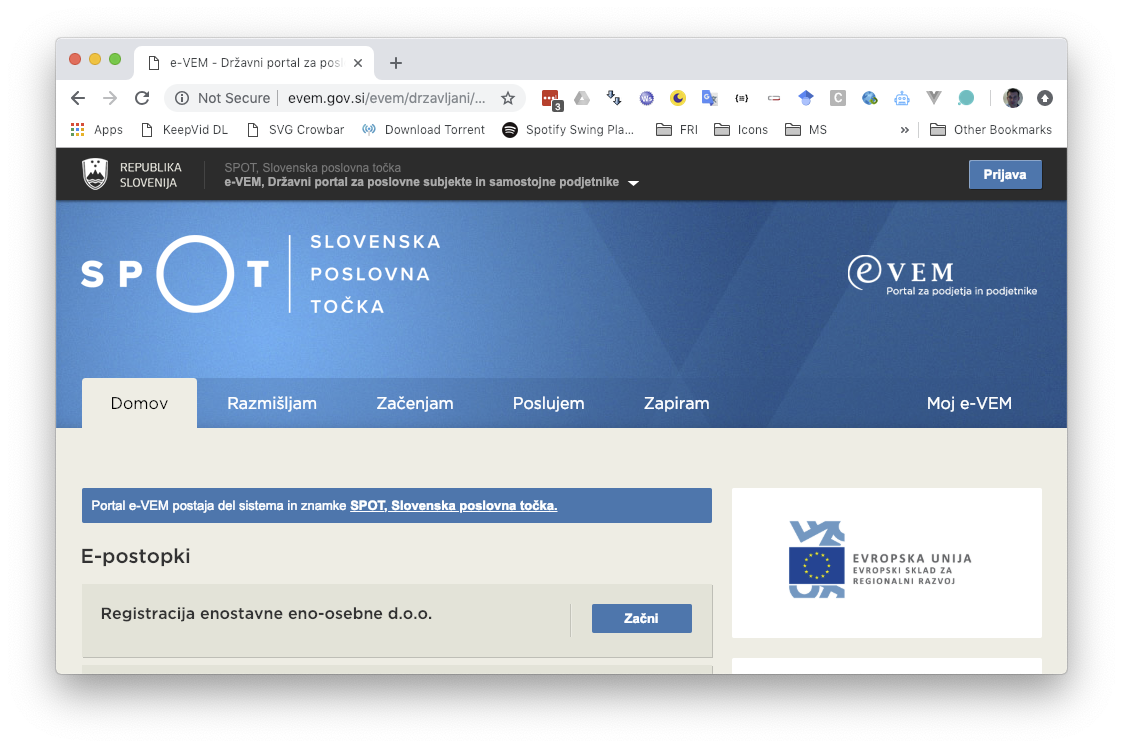

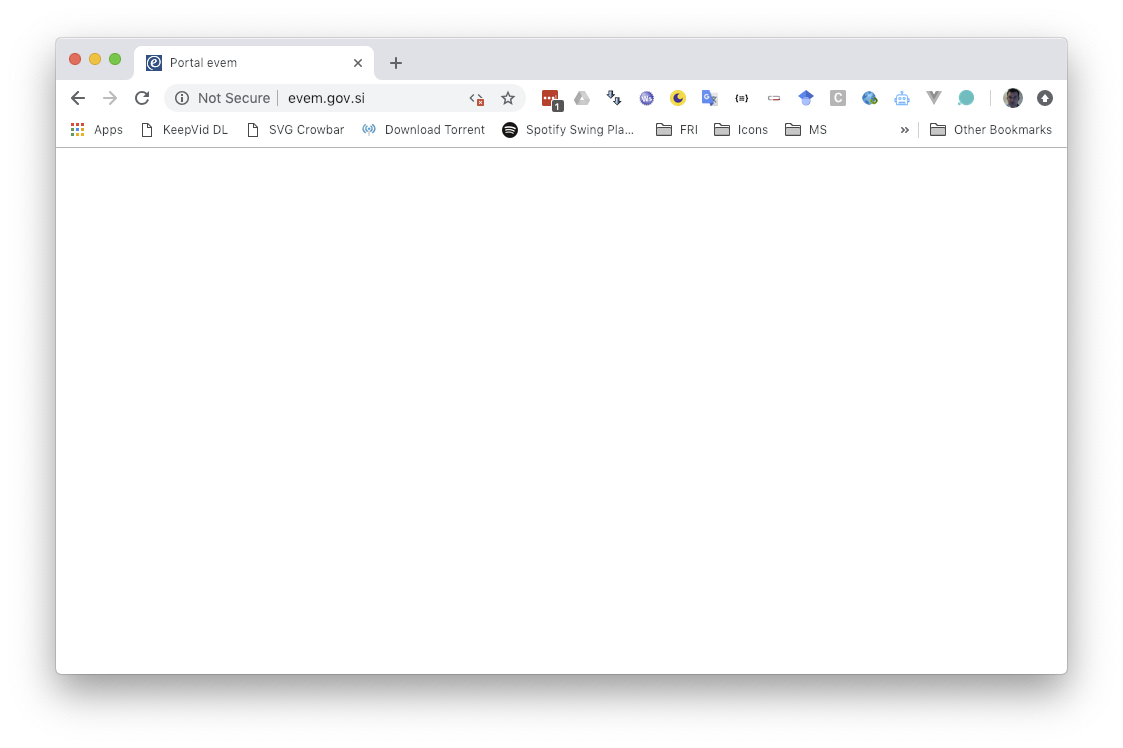

However, Web sites are becoming more dynamic - loading data in the background, not refreshing the entire view, etc. These functionalities require dynamic code to be executed directly on the client, that is, inside the Web browser. The main language that can be interpreted by a Web browser is Javascript. Although best practices instruct the programmers to support non-Javascript browsers, there are many Web pages that malfunction if the browser does not support Javascript. With the advent of Single page application (SPA) Web sites the content does not even partially load as the whole Web page is driven by the Javascript. Popular frameworks that enable SPA development are, for example Angular, Vue.js or React. Below we show some examples of rendering Web pages when a browser runs with Javascript enabled or disabled:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When we develop a Web extraction system we should first review how the target Web site is built and which frontend technologies are used. Then we can also more efficiently use a library to implement a final Web wrapper to extract the desired data. When we need to execute Javascript, our extraction library needs to implement headless browser functionality. This functionality runs a hidden browser to construct a final HTML content which is then used for further manipulation. Libraries that support such functionality are, for example:

- Selenium,

- Playwright,

- Puppeteer,

- phantomJS and

- HTMLUnit.

Currently (in 2025), Selenium and Playwright are the most widely used libraries. Selenium is mature library which allows for manual control of browser actions handling. Playwright on the other hand is newer (started in 2019) and enables more automatizations (e.g., automatic waits for dynamic contents), so therefore tends to be easier to use.

Running a headless browser and executing Javascript can be time consuming and prone to errors. So, whenever we can, we should rather use just an HTML parsing library. There exist many of such libraries and we mention just a few:

- HTML Cleaner,

- HTML Parser,

- JSoup (Java) or BeautifulSoup (Python),

- Jaunt API and

- HTTP Client.

4.2.4 Crawling, resources and policies

Crawling is a process of automatic navigation through Web pages within defined Web sites. When we deal with continuous retrieval of content from a large amount of Web pages, there are many aspects we need to take care of. For example,

- we need to track which pages were already visited,

- we need to decide how to handle HTTP redirects or HTTP error codes in case of a delayed retry,

- we must follow the rules written in robots.txt for each domain or should follow general crawling ethics so that we not send too many request to a specific server and

- we need to track changes on Web pages to identify approximate change-rate, etc.

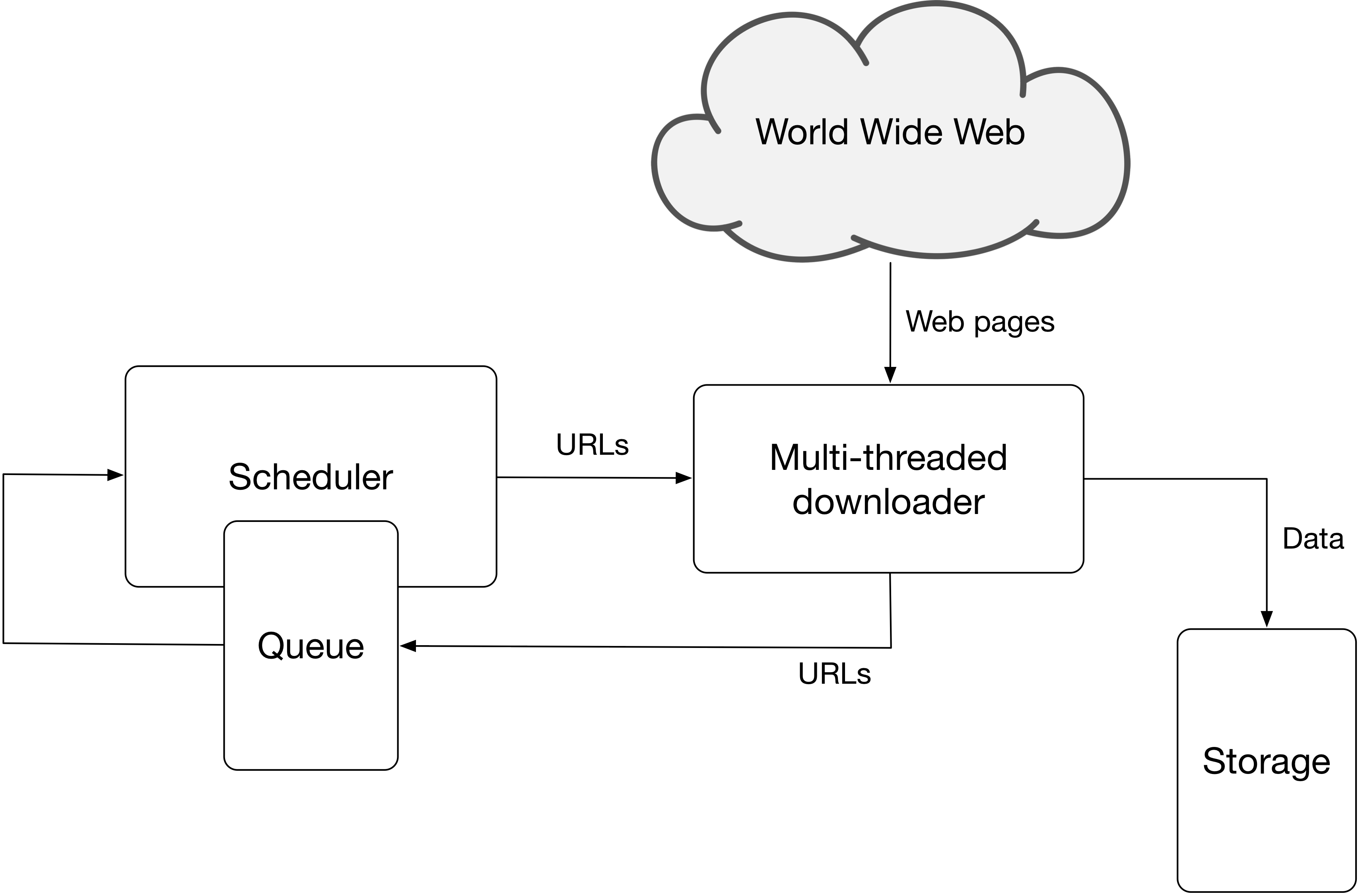

Generally, a crawler architecture will consist of the following components (Figure 4.2):

- HTTP downloader and renderer: To retrieve and render a web page.

- Data extractor: Minimal functionalities to extract images and hyperlinks.

- Duplicate detector: To detect already parsed pages.

- URL frontier: A list of URLs waiting to be parsed.

- Datastore: To store the data and additional metadata used by the crawler.

Figure 4.2: Web crawler architecture.

As we already mentioned before, we need to understand all the specifics how Web pages are built and generated. To make sure that we correctly gather all the needed content placed into the DOM by Javascript, we should use headless browsers. Google’s crawler Googlebot implements this as a two-step process or expects to retrieve dynamically built web page from an HTTP server. A session on crawling modern web sites built using JS frameworks, link parsing and image indexing was a part of Google IO 2018 and we recommend it to get an impression of problems that we can encounter:

A crawler needs to identify links, which can be encoded in several different ways. They can be explicilty given within href attributes, as onclick Javascript events (e.g. location.href or document.location), etc. Similarly, images can be generated in different formats, shown dynamically, etc. While in some circumstances it might be better to implement a custom crawler, a crawler package or suite is typically a better choice. Here are two examples:

The Web consists also of other files that web pages point to, for example PDF files, Word/OpenOffice documents, Excel spreadsheets, presentations, etc. They may also include some relevant information. We recommend the following tools for parsing such content:

- Apache Tika toolkit detects and extracts metadata and text from over a thousand different file types (such as PPT, XLS, and PDF). All of these file types can be parsed through a single interface, making Tika useful for search engine indexing, content analysis, translation, and much more.

- Apache Poi focus on manipulating various file formats based upon the Office Open XML standards (OOXML) and Microsoft’s OLE 2 Compound Document format (OLE2). In short, you can read and write MS Excel files using Java.

- Apache PDFBox library is an open source Java tool for working with PDF documents. This project allows creation of new PDF documents, manipulation of existing documents and the ability to extract content from documents. It also includes several command-line utilities.

4.4 Learning outcomes

Data science students should work towards obtaining the knowledge and the skills that enable them to:

- Understand the architecture and different technologies used in the World Wide Web.

- Use or build a standalone Web crawler to gather data from the Web.

- Identify and automatically extract the Web page content of interest.

4.5 Practice problems

- Explore the Web and find some dynamic Web sites. Inspect the structure of a few Web pages with your favorite browser and try to load the same Web pages with Javascript disabled. Go through basic Web crawling example and practise using the library as it allows for powerful features.

- Implement and run a crawler that will target https://fri.uni-lj.si/sl/o-fakulteti/osebje and extract the following information about every employee: name, email, phone number, title/job position and the number of courses they teach and number of projects they have listed. Save the data in CSV format.

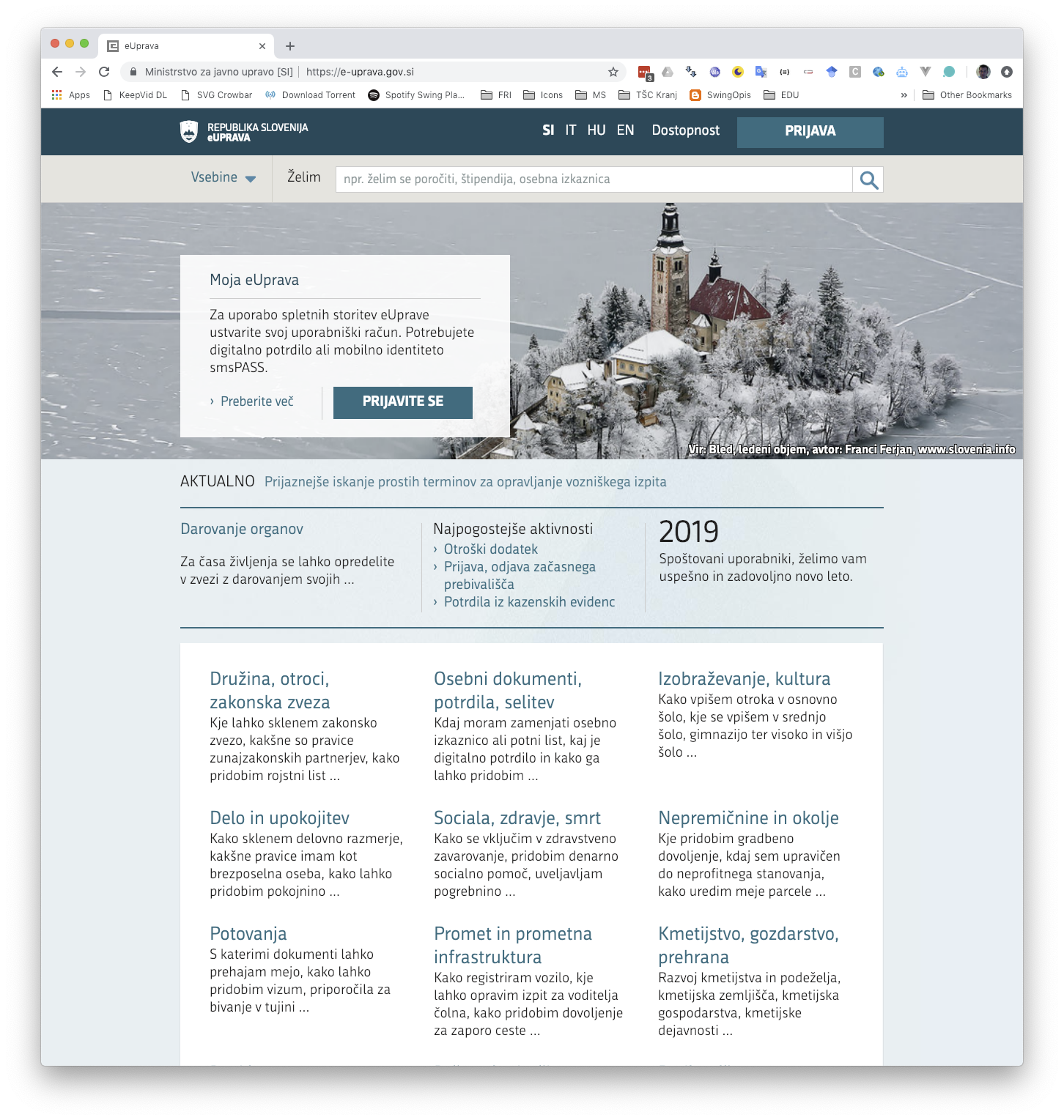

- An example project: Recently, gov.si Web site has been launched. Build a crawler that will retrieve semi-structured data from the site only. Also, you need to obey crawler ethics, take into account robots.txt, etc. Store rendered HTML data and also extracted data in a database.

- Use Selenium or Playwright to extract quotes (three different options) as described here: https://github.com/fri-datascience/course_ids/tree/master/data/WebScraping.